How has the job of the lighting designer changed over time? Having looked after CUTAZZ’s annual dance show for a long time now I thought I’d pause to reflect.

The first year I lit the show was all change – new lighting designer (muggins!), and a newly refitted Mumford theatre – so new lighting desk (ETC Ion) and a pile of Source 4 profiles. The new profiles have a much cooler beam and effectively mean gobos can now last forever – compare and constrast the following:

There was the usual constraint of having to send the lx plan in before having seen any run throughs. That first rig was a fairly traditional dance rig – as many colours of sidelight as the PAR can pile would allow, some shins, two colours of backlight, a breakup wash, some cyc colours. Specials were four gobos, a fan of 6 PAR Cans, two floods for some shadow-play on the cyc and three areas (DSL, DSR, MSC). Even back in 2011 I had a primitive visualiser (WYSIWYG design) so was able to draw a plan with confidence the focus would go well. Video had already found its way onto the techno-must-have list and I duly wandered off to video the two weekend run-throughs.

The brief from the company was simple back then – “most dances will consist of just one set lighting state throughout the dance. A few will require a little bit more but it will still only be 3/4 cues per dance. There are 21 dances in the show.” They were concerned about not over-running the three hour lighting plot and the costs of venue overtime. So preparing to plot was a two stage process – the first a “rough states” spreadsheet with one line per dance, capturing costume notes, possible colour combinations and any specials. From this a more detailed “cues” spreadsheet was built with fade times, notes for each state, approximate music and visual cues. Armed with this information the show was plotted over cans in the Mumford; venue tech on the Ion, me in the middle of the auditorium with my laptop. I surprised the company by sticking to the plot time – annoyingly it turned out there was a spare hour in the plan “because everyone overruns”(!) I hadn’t stuck to the “one state per piece” rule either though mostly where I hadn’t the states were easily related (state, add spot, remove spot, or alterating verse state vs chorus state). Plotting 117 cues in 3 hours is one every 90 seconds, or about 3 minutes to build from scratch, adjust and look at each state once you factor our the duplicates and the blackouts. I hate to think we used to plot this way. And don’t forget the three(!) effects – actually they were four but the latter was done manually with flash buttons.

That first year was well received; it was also an excellent spring-board for the following year. It’s always a massive advantage to have lit a venue or a similar show before; the 2012 rig was an evolution with many subtle changes based on learning from the previous year. The colour palette was updated – partly for colour changes but also to try and maximise the light output of the sidelight when covering a huge stage. Subtle tweaks to the backlight positioning and focus also led to more useable light on stage. Plus more time to think about adding gobos and changing the specials.

2012 was also the first year I’d stumped up for the full version of WYSIWYG Perform. The idea is simple enough – you connect your lighting desk offline editor to the Visualiser, and as you programme the show into the offline, the visualiser shows you what it looks like. Back then it was a revelation. No more truly “blind plot” – no more staring at a screen full of percentages and trying to imagine what it might look like. There was still the issue of the offline occasionally throwing out spurious DMX frames – it did this so you couldn’t use it instead of buying a real lighting desk. But the main issue was calibration – how would the show look like on stage vs in the visualiser? Fortunately this went well – the usual 3 hour frantic plot session replaced with “does this look ok? Next cue….”. The show had grown to 24 numbers and crept up to 150 lighting cues. Being able to plot at home meant being able to devote two whole days to the plot; time was still the enemy however as the offline editor is a rather slower thing to programme than the real lighting desk.

2012 was also the first year I had the pipe-tape printer – basically a 1:1 scale lighting plan you drop onto the lx bar. Also deployed for the first time on the dance show it lets you get lights positioned much more accurately – which is helpful when you have geometric beam patterns and the like. Hires that year extended to a haze machine and an Atomic 3000 Strobe.

2013 brought a small but welcome innovation – multiple cue lists in the lighting desk. All the dance numbers were now separate cue lists; more manageable, more logical and sensible cue numbers – and much easier to deal with when the company changes the running order. The only slight panic it caused was when the venue loaded all 227 lx cues into the desk but all the screen showed was “prestate, blackout”. Yes, now at 28 dance numbers and with the visualiser tamed the number of cues in the show had roughly doubled. 2013 also saw heavy use of Intensity Palettes in the pre-plot – making the Wednesday “quick look and fix” session more efficient. States that were meant to look the same now did having tweaked only the first of them. Likewise balancing four colours to get the intended colour mixing on the cyc only had to be done once per colour.

2014’s innovation was timecode. Until that point timing of cues had been via one of two means. Approximate timing in the music happened by someone watching the CD player and reading out the display over cans. Anything more precise required watching the dance rehearsal video and basically memorizing it. Together with the ability to offline visualise and plot it was getting to be quite a lot to remember and running the live show was nothing if not adrenaline filled. Timecode let me set cues exactly where I wanted them in the music – and with such accuracy it opened up whole new ways of plotting. Particularly for effects, flashes and big finishes things you would never dream of trying to do manually were now possible. 90% of the 246 cues were run this way the rest remaining as visuals. Timecode has its costs – it is hugely more time-consuming setting the cue points in pre-plot. One of its main advantages is that more of the dress rehearsal can be spent worrying about light levels and the look of the show – without also having to operate flash buttons, poke GO a zillion times and count eights and seconds in your head. Running the show brought very mixed emotions; delighted at how sharp the cues could be it is hard to describe how flat I felt after the first night. There’s something magic about opping a live show, focussing intently on the dance and the music, keeping a wary eye on the desk and generally trying to do a million things at once without cocking it up. I’m sure timecode is more reliable but it was way less fun. I did bits of the finale on flash buttons just to cheer myself up.

2015 saw the hire of a “proper” haze machine – able to go from “no haze” to “haze everywhere” in seconds. The main learning point was “don’t test this in the kitchen”

2016 was all change with the show moving from the Mumford to the Leys Great Hall. All the work of a new venue – positions, angles and focus, side and top masking all done from scratch. The rig was now a mixed LED and conventional rig. And with two washes of colour-changing units for the backlight and sidelight you end up with far fewer units. The first show in the Leys weighed in at 87 lights (all the Mumford rigs had been over a hundred units). You have less to focus when one wash can do any colour but it costs you time checking your colours actually look nice. I’d settled on a palette of about 16 colours; the new hell being to keep a clear idea in my head what colour I wanted them to be in the venue (different to what the visualiser thought they looked like, which was different again to what the lighting desk’s colour picker thought they looked like). One day the world will calibrate this stuff properly! There’s more setup too – the lights have fixture modes, dimming curves and other parameters to manage; the 87 control channels plus the venue house lighting end up mapped across five universes of DMX in total. On the plus side it was great not to be reliant on three colours of PAR can for the sidelight; on the minus the LED light quality simply isn’t as nice as tungsten or discharge. It’s hard to say what’s missing – but something definitely is.

I also discovered Show Cue System in 2016; no more having to find an Apple Mac just to run timecode in QLab. It’s quite a capable bit of software and its pricing and license model are very reasonable.

2017 got off to an expensive start with the purchase of a programming wing. It’s equivalent to the main control surface of the lighting desk minus all the submaster faders. Together with two touch-screens it makes offline plotting a lot easier than with a QWERTY keyboard. It can also spit out real DMX and Ethernet control frames – no more visualizer glitches from “offline” mode. Unlike the normal offline editor it also connects to real external MIDI sources – so for the first time it was possible to test the timecoding (Show Cue System + MIDI + lighting desk + visualizer) prior to leaving for the venue. Also on the expensive list was a GoPro camera. I first bought a video camera for rehearsal in 2009 – it had been a massive help and a great productivity boost; however, you always ended up filimg rehearsals rather than watching them. And rehearsal rooms are never large enough – you end up filming from at most a metre in front of the “stage” space. Hence the massively wide-angle GoPro – now the camera just sits there and captures everything and I can concentrate on making notes and thinking about what I’m watching.

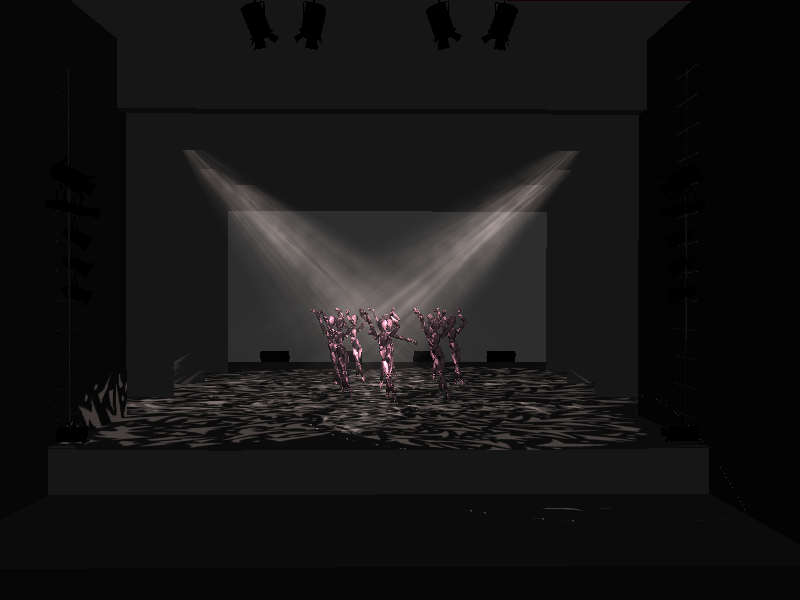

And 2018? We made hanging booms work at the Leys. So now the colour-key sidelight is much closer to body height but not so low it causes problems with entrances and exits. And it’s in a different place and from a different angle to the general lavender wash – so the two compliment each other rather than washing each other out. Not rocket science but still a welcome improvement. Also, a full 19 years after I’d first put moving lights in a show, we eeked out the budget to include two movers. Ok they only picked off some of the specials but it hints at a world where such things are more affordable and if cost can be squeezed out elsewhere it’s possible they could be more of a feature in future years.

Overall then a lot has changed. The basics are quicker and easier and the tools are better – but more can be done with them and more is possible – indeed expected. The unchanging thing is that time is still the enemy: there are 50 percent more dance numbers in the show and four times as many lighting cues but there’s still only the Monday and Tuesday between first seeing the show in costume and having to be plotted. The world has changed around us too – a non-moving light design tends to be the exception not the rule today and people are used to the eye candy they see on television and at live events – the show has some catching up to do here. I’m glad to say some things haven’t changed – the nuts and bolts of colours and angles and how they play with form and movement are still important; the dance is ever changing and the performers’ enthusiasm undimmed. The live spectacle is always something special.

Really enjoyed reading this one, very interesting 🙂

LikeLike

Really enjoyed reading this!

LikeLike

It makes a great read, thanks for taking the time to write it up!

LikeLike